Why the 'Passion'? What's Tenebrae? And why does Easter's date change?

CHARLOTTE — Sometimes the words we use in Holy Week and Easter feel so familiar we don't consider their origins. Same for the date of Easter, which changes from year to year. The following is a quick FAQ guide to Catholics' Holy Week vocabulary and key history.

CHARLOTTE — Sometimes the words we use in Holy Week and Easter feel so familiar we don't consider their origins. Same for the date of Easter, which changes from year to year. The following is a quick FAQ guide to Catholics' Holy Week vocabulary and key history.

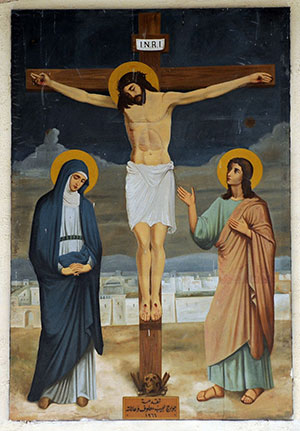

Q. Why do we use the word "Passion" to describe the suffering of Jesus?

A. The word "Passion" comes from the Latin word for suffering. When referring to the events leading up to the death of Jesus, we often capitalize the word "Passion" to differentiate from the modern meaning of the word with its romantic overtones.

Q. Why do some parishes cover the cross and statues during Holy Week?

A. Before 1970 it was customary to cover crosses and statues during the last two weeks of Lent. After 1970, the practice was left up to the discretion of each diocese. In 1995, the U.S. bishops' liturgy committee gave individual parishes permission to reinstate the practice on their own.

Q. What is Tenebrae?

A. The word "tenebrae" comes from the Latin word meaning "shadows" or "darkness." It was originally the name given to somber parts of the Liturgy of the Hours that are chanted in monasteries on the last three days of Holy Week. The tone of the prayers is filled with sorrow and desolation. At various points during a Tenebrae service, candles are extinguished and there is a cacophony of noise, which evokes feelings of betrayal, abandonment, pain, sadness, and darkness associated with the crucifixion and death of Jesus. Parishes sometimes offer Tenebrae services during Holy Week.

Q. Why do we call it "Good Friday"?

A. In the English language the term "Good Friday" probably evolved from "God's Friday" in the same way that "goodbye" evolved from "God be with you."

Q. Why do some parishes celebrate the Good Friday liturgy in the afternoon and others in the evening?

A. Ideally, the liturgy should take place at 3 p.m. However, in order to encourage more people to attend, the liturgy can take place later in the evening, but never after 9 p.m.

Q. What is Pascha?

A. The word "Pascha," or "Pasch," comes from the Greek word for the Passover. The early Christians used the word to describe the resurrection of Jesus as the Christian Passover. Today, we sometimes refer to the death and resurrection of Jesus as the Paschal Mystery, which is derived from the word Pasch. Orthodox Christians still use the word Pascha when referring to Easter.

Q. Who decides the date of Easter?

A. In 325, the Council of Nicaea decreed that Easter would be celebrated on the Sunday following the first full moon after the spring equinox. It can occur as early as March 22 or as late as April 25.

— Lorene Hanley Duquin. Lorene Hanley Duquin is a Catholic author and lecturer who has worked in parishes and on a diocesan level.

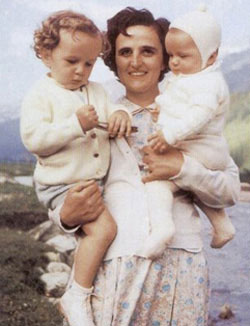

St. Gianna Beretta Molla, patron saint of mothers, physicians and unborn children, is pictured with two of her four children.St. Gianna Beretta Molla was an Italian pediatrician born in Magenta in the Kingdom of Italy on Oct. 4, 1922. She was the 10th of 13 children in her family.

St. Gianna Beretta Molla, patron saint of mothers, physicians and unborn children, is pictured with two of her four children.St. Gianna Beretta Molla was an Italian pediatrician born in Magenta in the Kingdom of Italy on Oct. 4, 1922. She was the 10th of 13 children in her family.

At 3 years old, she and her family moved to Bergamo, and she grew up in the Lombardy region of Italy.

As a young girl, she embraced her faith and the Catholic-Christian education provided to her from her loving parents. She grew up viewing life as God's beautiful gift and found the greatest necessity and effectiveness in prayer.

In 1942, she began the study of medicine in Milan. She was a diligent and hardworking student, both at the university and in her faith.

As a member of the St. Vincent de Paul Society, Gianna applied her faith in an apostolic service for the elderly and needy.

She earned degrees in both medicine and surgery from the University of Pavia in 1949, and in 1950 she opened a medical office in Mesero, near her hometown of Magenta.

In 1952, Gianna specialized in pediatrics at the University of Milan and from there on, she was especially drawn toward mothers, babies, the elderly and the poor.

Gianna considered the field of medicine to be her mission, and treated it as such. She increased her generous service to Catholic Action, a movement of lay Catholics dedicated to living and spreading the Social Teaching of the Catholic Church in the broader culture. The Catholic Action movement is still at work today, throughout the world.

Gianna hoped to join her brother, a missionary priest in Brazil, where she intended to offer her medical expertise in gynecology to poor women.

However, her chronic ill health made this impractical, and she continued her practice in Italy.

She chose the vocation of marriage and considered this to be a gift from God. Gianna embraced this gift with all her being and completely dedicated herself to “forming a truly Christian family.”

In December 1954, Gianna met Pietro Molla, an engineer who worked in her office. They were officially engaged the following April, and married in September 1955, making Gianna a happy wife.

Gianna wrote to Pietro, “Love is the most beautiful sentiment that the Lord has put into the soul of men and women.”

In November 1956, Gianna became a mother to her first child, Pierluigi. They welcomed a second child, Maria Zita, in December 1957, and a third, Laura, in July 1959.

Gianna handled motherhood with grace and was able to harmonize all aspects of her demanding life.

In 1961, Gianna became pregnant with her fourth child. Toward the end of her second month of pregnancy, Gianna was struck with an unimaginable pain.

Her doctors discovered she had developed a fibroma in her uterus, meaning she was carrying both a baby and a tumor.

After examination, the doctors gave her three choices: an abortion, which would save her life and allow her to continue to have children, but take the life of the child she carried; a complete hysterectomy, which would preserve her life, but take the unborn child's life, and prevent further pregnancy; or removal of only the fibroma, with the potential of further complications, which could save the life of her baby.

Catholic teaching affirms what medical science, natural law, the Bible and unbroken Christian tradition affirm: the child in the womb has a fundamental human right to life. Wanting to preserve her child's life, Gianna opted for the removal of only the fibroma.

In fact, she was willing to give her own life to save the life of her child.

Gianna pleaded with the surgeons to save her child's life over her own. She sought comfort in her prayers and her faith.

The child’s life was saved, for which Gianna graciously thanked the Lord.

After the operation, complications continued throughout her pregnancy, but Gianna spent the remainder of her pregnancy with an unparalleled strength and insistent dedication for her tasks as a mother and a doctor.

A few days before the baby was to be born, Gianna prayed the Lord take any pain away from the child. She recognized she may lose her life during delivery, but she was ready.

Gianna was quite clear about her wishes, expressing to her family: “If you must decide between me and the child, do not hesitate: choose the child? I insist on it. Save the baby.”

On April 21, 1962, Gianna Emanuela Molla successfully delivered by Caesarean section.

The doctors tried many different treatments and procedures to ensure both lives would be saved. However, on April 28, 1962, a week after the baby was born, Gianna passed away from septic peritonitis. She is buried in Mesero.

Gianna was beatified by Pope John Paul II on April 24, 1994, and officially canonized as a saint on May 16, 2004. Her husband and their children, including Gianna Emanuela, attended her canonization ceremony, making this the first time a husband witnessed his wife's canonization.

In 2003, mother-to-be Elizabeth Comparini experienced a tear in her placenta when she was 16 weeks pregnant. Her womb was drained of all amniotic fluid. She was told the chances of her baby’s survival was little to none. Elizabeth is said to have prayed to Gianna Molla and asked for her intercession. Elizabeth later gave birth to a healthy baby.

During Gianna's canonization ceremony, the pope described her as “a simple, but more than ever, significant messenger of Divine Love.”

St. Gianna is the inspiration behind the first pro-life Catholic healthcare center for women in New York, the Gianna Center.

St. Gianna Beretta Molla is the patron saint of mothers, physicians, and unborn children. Her feast day is celebrated on April 28.

— www.CatholicOnline.com