The ‘other Marys’ behind the ‘other Christs’

Father John Eckert with his mother, Cheryl Eckert, at St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican CityMotherhood is a mystery: From the moment a woman learns she is pregnant, she may wonder what God has in store for the little soul she shelters, and a world of possibilities opens in front of her as she cooperates with God in His act of creation. Among Catholics, there is a special motherly vocation that is closely configured to the Blessed Virgin Mary: the mother of a priest.

Father John Eckert with his mother, Cheryl Eckert, at St. Peter's Basilica in Vatican CityMotherhood is a mystery: From the moment a woman learns she is pregnant, she may wonder what God has in store for the little soul she shelters, and a world of possibilities opens in front of her as she cooperates with God in His act of creation. Among Catholics, there is a special motherly vocation that is closely configured to the Blessed Virgin Mary: the mother of a priest.

Many mothers of priests live – and pray – the joyful, luminous, sorrowful and glorious mysteries of the rosary in a unique way, imitating Mary in their faithfulness, humility and prayer. They foster faith-filled homes where their sons grow and draw closer to Jesus, the Eternal High Priest, and one day formally dedicate their lives as “other Christs,” ministering to His people. The joys, these mothers say, far outweigh the sorrows.

St. Pius X may have put it best when, from personal experience, he said, “A vocation comes from the heart of God, but goes through the heart of the mother.”

Of his sainted mother Monica, St. Augustine, a bishop and Doctor of the Church, once wrote, “What I became and what I am, I owe to the prayers and merits of my mother.”

Throughout the centuries, these sentiments have been shared by countless priests who became saints, including John Bosco, Bernard of Clairvaux and John Paul II.

It’s true today in the Diocese of Charlotte, too. Recently the mothers of Father Andrés Gutiérrez, a missionary priest in Peru whose family belongs to Our Lady of Grace Parish in Greensboro; Father John Eckert, pastor of Sacred Heart in Salisbury; and Father Noah Carter, pastor of Holy Cross in Kernersville, shared their perspectives about this special calling with the Catholic News Herald.

These moms’ memories and experiences were as unique as the men they helped raise, but they all have in common a rock-solid faith in God and a deep devotion to Our Blessed Mother.

“A mother’s prayers are very powerful for all her children and for every vocation,” says Father Gutiérrez’s mother, Martha Lucia. “Try it, and you’ll see.”

An unexpected calling Father Andrés Gutiérrez with his parents and brothers at his high school graduationThe middle son of Fernando and Martha Lucia Gutiérrez gave his parents the surprise of a lifetime when he called them one day to give them an update. They fully expected to hear that he was going to get married, but 25-year-old Andrés told them he was going to become a missionary priest instead.

Father Andrés Gutiérrez with his parents and brothers at his high school graduationThe middle son of Fernando and Martha Lucia Gutiérrez gave his parents the surprise of a lifetime when he called them one day to give them an update. They fully expected to hear that he was going to get married, but 25-year-old Andrés told them he was going to become a missionary priest instead.

“It was a total surprise,” Martha Lucia says. Despite all indications to the contrary at the time, she now understands that he had been discerning things in his mind and heart for a long time.

Martha Lucia never openly encouraged the priesthood, but the Gutiérrezes did consecrate their family, including each of their three sons, to Jesus through the Immaculate Heart of Mary.

Born in Colombia, the future Father Andrés Gutiérrez moved to Spain with his family when he was 2 and lived there for about seven years before the family relocated to south Florida. Martha Lucia took care to make their home one filled with faith.

“I would encourage parents to motivate the kids to religious life. They don’t have to be a priest, just encourage spiritual life at home,” Martha Lucia says. “We always had a small altar with the Virgin, a crucifix, flowers and holy water. We made it part of our daily lives as much as we could. When you do that, I think they keep it.”

Seeds of Father Gutiérrez’s vocation were planted in college when he went on a three-week mission trip to Cusco, Peru. His discernment continued slowly, however. He finished college with a master’s degree, began working for Intel Corp. in Arizona, and had a good, very Catholic girlfriend.

He started questioning what God was calling him to do and ultimately decided to study for the priesthood. He was ordained in Peru in 2015 for the Archdiocese of Cusco, where he still ministers today as pastor of St. Martin de Porres Parish.

His mother insists that all she did was pray for each of her children. She says sometimes being the mother of a priest makes her more conscious of herself. “Other people think that you have to be different or special, and it’s not true. You’re the same, always,” she says.

Father Gutiérrez, on the other hand, notes his mother’s special gifts, especially in the way she nurtured and guided all her children.

“Without the exemplary selflessness of my parents, I would not be a priest. In my mother, that translated to an unlimited and unconditional disposition of service to us, her children,” he says. “I just can’t recall an instance where she did something for herself or her diversion. Her only motivation and joy was her family, always ready to give of herself what we needed, when we needed it: to drive us here and there, to correct when correction was needed, to nurture and guide in the paths of goodness and virtue.”

“Without the exemplary selflessness of my parents, I would not be a priest. In my mother, that translated to an unlimited and unconditional disposition of service to us, her children,” he says. “I just can’t recall an instance where she did something for herself or her diversion. Her only motivation and joy was her family, always ready to give of herself what we needed, when we needed it: to drive us here and there, to correct when correction was needed, to nurture and guide in the paths of goodness and virtue.”

He continues, “I would also highlight her wisdom and intuition, paired with my dad’s prudence and faith, that led me specially to structure a personal world view based on faith and virtues and avoid many of the dangers inherent in growing up.”

Noting the many spiritual activities they participated in as a family like the rosary and weekly Holy Hours of Adoration, Father Gutiérrez says the faith never felt overly forced or imposed because it was lived out naturally. Father Andrés Gutiérrez with his mother, Martha Lucia, and brothers Guillermo and Javier at Guillermo's wedding

Father Andrés Gutiérrez with his mother, Martha Lucia, and brothers Guillermo and Javier at Guillermo's wedding

“She always clearly respected our individuality and created an environment for the healthy growth of our free will. I think this is quite remarkable, as I now see how difficult it is for parents to strike this balance. It speaks volumes of my mom and the grace of God at work in her.”

Though he is only able to visit Greensboro once or twice a year, Martha Lucia says she and Fernando have been able to watch Father Gutiérrez offer Sunday Mass online. Together, they frequently pray the rosary and a novena for their son and his ministry.

Says Father Gutiérrez, “When I embarked on this divine adventure at the age of 25, I cannot doubt that her prayers and sacrifices – hidden from the spotlight – have accompanied and sustained me every step of the way. Praise God for mothers!”

Destined for the priesthood

As soon as Kathryn O’Brien learned her daughter Cheryl was expecting a baby boy, she announced, “He’s going to be a priest!”

Three years later in 1984, that little boy, the son of John Sr. and Cheryl Eckert, had his defense ready on the playground in Peoria, Ill., when a young girl approached him and said, “Johnny Eckert, I’m going to kiss you.” The future Father John Eckert stopped her in her tracks and said, “No, I’m going to be a priest.”

Father John Eckert as a preschooler and his mom, Cheryl Eckert“It was one of those things that he just knew from a very young age,” says his mother Cheryl. “As a young child, he could always communicate well with adults and then, as he was growing up, he could always communicate with young kids. He was sensitive to others and very empathetic.”

Father John Eckert as a preschooler and his mom, Cheryl Eckert“It was one of those things that he just knew from a very young age,” says his mother Cheryl. “As a young child, he could always communicate well with adults and then, as he was growing up, he could always communicate with young kids. He was sensitive to others and very empathetic.”

The eldest of four children, Father Eckert has always felt at home in the Church.

“There was never, never a point where he was just going through the motions, and a lot of people saw that in him,” his mother recalls. “At the parish we belonged to until he was 10 years old, the assistant priest chose him to be one of the ones to get his feet washed on Holy Thursday, which was very unusual for them to pick a child. He wasn’t even old enough to be a server.”

Like the Blessed Virgin Mary, Cheryl pondered these things in her heart.

Though he considered entering the seminary after high school, the young John Eckert ultimately decided to go to college at Saint Louis University where he had many friends, including a girlfriend. He double majored in political science and communication and was ranked highly in his class.

“He had the world at his feet. He could have done anything or gone anywhere, and so at that point it was a choice,” Cheryl says.

Though he considered graduate school, he ultimately decided to enter the seminary at Pontifical College Josephinum in Ohio and was ordained in the Diocese of Charlotte in 2010.

“I was very happy with the way things turned out,” his mother says.

Grandma O’Brien was pleased, too.

Father Eckert says he never felt pressure to enter the seminary but knew his parents would support him.

“I make the joke that I predate being a cradle Catholic, that I’ve been Catholic since conception just because of the way they are and how good my parents have been,” Father Eckert says. “The openness and the love of the faith that's been present from the very beginning is so good. My mom and my grandma being so faithful themselves also made a difference.”

He continues, “My parents never made us go to Mass. They made us want to go to Mass. It was part of the air we breathed, the water we drank. It was a good environment to discern the priesthood.”

Father John Eckert with his family at his ordination Mass in 2010Father Eckert became the pastor of Sacred Heart Parish in Salisbury in 2014, and his parents, who live 40 minutes away in Charlotte, became parishioners in 2016. Like the mother of St. John Bosco who helped her son in his mission, Cheryl donates her time and talent to her son’s ministry as the parish’s bookkeeper.

Father John Eckert with his family at his ordination Mass in 2010Father Eckert became the pastor of Sacred Heart Parish in Salisbury in 2014, and his parents, who live 40 minutes away in Charlotte, became parishioners in 2016. Like the mother of St. John Bosco who helped her son in his mission, Cheryl donates her time and talent to her son’s ministry as the parish’s bookkeeper.

With her significant business experience, including bookkeeping for St. Thomas Aquinas Parish in Charlotte and her work in their previous hometown of Peoria, she is a welcome resource.

“It’s good to be able to bounce things off my mother. I know she’s going to tell me the truth,” Father Eckert says. “She’s been such a huge help navigating a time at the parish where we had some very significant debts, and then to have her generosity coming on as a volunteer has been incredible.”

In February, Father Eckert’s parents joined him on the parish pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Two days after their return, he experienced a terrible sickness.

“I got hit with some stomach bug, which was atrocious, and just had me you know down for the count,” he says. “Well, I got to go home to my parents’ house, and they took good care of me. To have your mom taking good care of you when you're sick like that, is a huge gift that not everybody gets, especially as an adult.”

Recently, a Seven Sisters Apostolate was established at the parish. This involves seven women who commit to one Holy Hour each week dedicated to praying for their pastor. In ministries like these, any woman can “mother” a priest by spiritually adopting him in prayer.

“It’s a very humbling gift to know that I’m being so intentionally supported in that way. To know that I’ve got that kind of support is just beautiful,” Father Eckert says. “I’m glad my mom joined this group of women in the parish. At the same time, I know she has been praying for me forever. I am grateful for her every day.”

A beautiful answer to a mother’s prayer

Father Noah Carter with his mother, Holly Carter, and his two older brothersThe cross has been near ever since the earliest days of Father Noah Carter’s life.

Father Noah Carter with his mother, Holly Carter, and his two older brothersThe cross has been near ever since the earliest days of Father Noah Carter’s life.

“In the hospital, about 20 to 30 minutes after feeding, he would become ashen and blue and have trouble breathing,” recalls his mother, Holly Carter. “So at that point in time, I just had this prayer that whatever it took, whatever God wanted from me, I would do. I prayed, ‘If You save this child, I will raise him in Your hands.’”

The doctors placed baby Noah on an apnea monitor to track his heart rate and breathing, and he remained on it for seven months after the day of his birth, which happened to be Sept. 14 – the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross.

“You had to wire him up,” Holly remembers. “If he wasn’t wired up to the machine, you had to hold him.”

As heart-wrenching as the medical intervention was, Greg and Holly Carter were also living the joyful mysteries at the birth of their youngest son. All the while, God kept Holly’s promise in mind.

At the time, Holly was Episcopalian but was feeling drawn to the Catholic faith. She converted three years after Noah was born because she wanted to raise their children in a one-religion household. The life of the Church came before any outside activities and even before school when altar servers were needed for a funeral at their parish, St. Barnabas in Arden.

“I was very mindful of what my boys experienced and what they were involved in,” she says. “They could pick just one extracurricular activity outside the church.”

Growing up, the family read from the Books of Wisdom and Proverbs at home, and young Noah was already showing a strong interest in the Mass at age 7.

“Every once in a while, we would go to the 5:30 Mass on Saturday, and he was exhausted and would lie down on the kneeler and I told him it was OK to lie on the kneeler, but he had to be awake and had to be present,” his mother says. “I would have to hush and shush him because he would be saying the words of the entire Eucharistic Prayer with the priest. So, in my mind, I needed to be more aware and conscious of his involvement in the Church.”

As their son continued to show interest in the priesthood throughout his teen years, Greg and Holly helped him explore how to make that happen.

“I had a sense that this is what God was calling us to, because a priest doesn’t come up by himself,” Holly says. “My heart was just so overflowing with grace and fullness knowing that that’s what he really felt he might be called to. I was so happy that he was seriously considering it and that he wasn’t afraid.”

Father Carter recalled his mom’s influence throughout his childhood.

Father Noah Carter with his parents, Greg and Holly Carter, at his ordination Mass in 2014“In the many conversations we had growing up, my mom was really the one who would encourage me to step back and really ponder things and pray about them before I did anything. She was that voice of reason and spirituality,” he says. “That didn't mean that I wasn't very impulsive like most kids are and would do stupid things. Yet she was the one who always had that sense of, ‘It's not an emergency yet, so don't act like it is, and be more reflective on the choices you're making.’”

Father Noah Carter with his parents, Greg and Holly Carter, at his ordination Mass in 2014“In the many conversations we had growing up, my mom was really the one who would encourage me to step back and really ponder things and pray about them before I did anything. She was that voice of reason and spirituality,” he says. “That didn't mean that I wasn't very impulsive like most kids are and would do stupid things. Yet she was the one who always had that sense of, ‘It's not an emergency yet, so don't act like it is, and be more reflective on the choices you're making.’”

Ultimately, he decided to enter the seminary at Pontifical College Josephinum in Ohio after high school. He was still 17.

“He graduated in June, his father took him up to seminary in July, and as far as I was concerned, that’s when my heart had to say, ‘I have fully turned him over to God and to the diocese and put my trust in God and the diocese to take care of my child,’” Holly recalls.

That year, the seminarians’ education session ended on Mother’s Day, and Holly went to pick up her son and attend Mass. “It was perfect. When I met the other young men, I was so glad he had them alongside him,” she says.

Father Carter says that four years later he was sent to Rome to study.

Father Noah Carter blesses his mother at his first Mass“My parents couldn’t go at the time,” he recalls. “They had to put me on a plane and weren’t going to see me for 18 months, but my mom was always strong and very much resigned to this being how a family sacrifices when a child has a call to the priesthood.”

Father Noah Carter blesses his mother at his first Mass“My parents couldn’t go at the time,” he recalls. “They had to put me on a plane and weren’t going to see me for 18 months, but my mom was always strong and very much resigned to this being how a family sacrifices when a child has a call to the priesthood.”

Father Carter was ordained a deacon in Rome in 2013 and to the priesthood in the Diocese of Charlotte a year later. He noted his mother’s wonderful spirit of hospitality at their home, especially following his ordination, and the way she paid particular attention to ensuring everything was in order for his first Mass. In 2019, on the feast of St. John Vianney, he became pastor of his first parish: Holy Cross in Kernersville, where he serves today.

In 2020, Father Carter contracted COVID-19 and suffered heart complications. His mother was highly concerned and offered to come help. At first, he said she didn’t need to come because he was doing alright.

Holly understood and was prepared to honor her priest son’s wishes even as the memories of her son’s first days came flooding back. That's when Father Carter's brother Zach intervened and called him to say, “You’ve got to let Mom come. You may not need it, but she does.”

Holly soon arrived to care for her son for the first week of his three-month medical rest. “When I was still very weak, and we were waiting for my heart to get back up to 100 percent, it was so good to have that downtime and to spend it with my mom,” Father Carter says.

Father Carter stays involved in the lives of his family members, including his young nieces. When it comes to his mother, their bond is extra close.

Holly says, “I watch his hands and face, and to me, it looks like he has a lot of my mannerisms. I have a friend who goes to St. Margaret in Swannanoa, and she agrees. After he came to do their parish mission, she told me, ‘It was like I could see you standing behind him.’”

In this special vocation within motherhood, every priest’s mother similarly stands behind her son in spirit with the Blessed Virgin Mary. As the mother of all priests, Mary remains present with them at the altar as she stood by her Son at the foot of the cross – praying, consoling and rejoicing with each of them throughout their lives.

— Annie Ferguson

Gift of the manutergium

Father Noah Carter with his hands wrapped in the manutergium after being anointed by the bishop at his ordination in 2014Ordination is a momentous, solemn occasion in the lives of men called to be priests. It’s a major event for his family, too, especially for his parents. Did you know that they each receive a special keepsake from their son’s ordination?

Father Noah Carter with his hands wrapped in the manutergium after being anointed by the bishop at his ordination in 2014Ordination is a momentous, solemn occasion in the lives of men called to be priests. It’s a major event for his family, too, especially for his parents. Did you know that they each receive a special keepsake from their son’s ordination?

His father receives the purple stole his son wears when he hears his first confession after ordination. And his mother receives the linen cloth used to clean the new priest’s hands after being anointed with sacred chrism.

The priest presents the cloth, called a manutergium, to his mother after offering his first Mass. She keeps it for the rest of her life and is buried holding it in her hands. According to tradition, when the priest’s mother comes before Christ at her judgment, He says: “I have given you life. What have you given to me?” She hands him the manutergium and responds, “I have given you my son as a priest.” Heaven is her reward.

Though lost for a time, this tradition has been revived among priests in recent years.

Holly Carter says she keeps her son’s manutergium cloth in a white heart-shaped box and has made sure her husband Greg knows where it is. “Every once in a while, I get that box out – I’m sure all priest mothers do – and I just take and smell it,” she says with a smile. “You know, it’ll be just heavenly to go to heaven in that position.”

Cheryl Eckert has also set aside her son’s manutergium, framed in a shadowbox, and periodically takes it out to enjoy the fragrant scent of the sacred chrism and reflect on her son’s ministry.

With a beaming smile, Martha Lucia Gutiérrez adds that from time to time she too takes out her son’s manutergium from the special place she keeps it.

With a beaming smile, Martha Lucia Gutiérrez adds that from time to time she too takes out her son’s manutergium from the special place she keeps it.

“There’s a feeling that it brings you,” she says. “It reminds me of his ordination. It is so touching to leave that ceremony, because he lays down as any other person in the world and gets up as a priest. That is something that many people just can’t comprehend.”

— Annie Ferguson

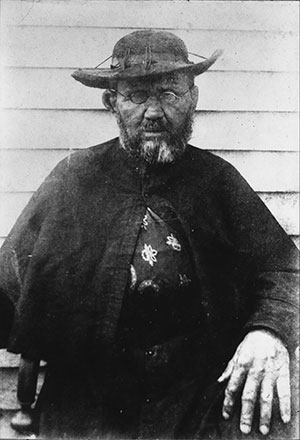

The Church will remember St. Damien of Molokai May 10. The Belgian priest sacrificed his life and health to become a spiritual father to the victims of leprosy quarantined on a Hawaiian island.

The Church will remember St. Damien of Molokai May 10. The Belgian priest sacrificed his life and health to become a spiritual father to the victims of leprosy quarantined on a Hawaiian island.

Joseph de Veuser, who later took the name Damien in religious life, was born into a farming family in the Belgian town of Tremlo in 1840. During his youth he felt a calling to become a Catholic missionary, an urge that prompted him to join the Congregation of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary.

Damien's final vows to the congregation involved a dramatic ceremony in which his superiors draped him in the cloth that would be used to cover his coffin after death. The custom was meant to symbolize the young man's solemn commitment, and his identification with Christ's own death. For Damien, the event would become more significant, as he would go on to lay down his life for the lepers of Molokai.

His superiors intended to send Damien's brother, a member of the same congregation, to Hawaii. But he became sick, so Damien arranged to take his place. Damien arrived in Honolulu in 1864, less than a century after Europeans had begun to establish a presence in Hawaii. He was ordained a priest the same year.

When he had been a priest for nine years, Father Damien responded to his bishop's call for priests to serve on the leper colony of Molokai.

Their lack of previous exposure to leprosy, which had no treatment at the time, made the Hawaiian natives especially susceptible to the infection. Molokai became a quarantine center for the victims, who became disfigured and debilitated as the disease progressed. The island had become a wasteland in human terms, despite its natural beauty. The leprosy victims faced hopeless conditions and extreme deprivation, sometimes lacking not only basic palliative care but even the means of survival.

Inwardly, Damien was terrified by the prospect of contracting leprosy himself. However, he knew that he would have to set aside this fear if he were to convey God's love to the lepers. Other missionaries had kept the lepers at arms' length, but Damien chose to immerse himself in their lives and leave the outcome to God.

The leprosy victims saw the difference in the new priest's approach and embraced his efforts to improve their living conditions. A strong man, accustomed to physical labor, Damien performed the Church's traditional works of mercy – feeding the hungry, sheltering the homeless, and giving proper burial to the dead – in the face of suffering that others could hardly even bear to see.

His work helped to raise up the lepers from their physical sufferings, while also making them aware of their worth as beloved children of God. Although he could not take away the constant presence of death in the leper colony, Damien could change its meaning and inspire hope.

The priest's devotion to his people, and his activism on their behalf, sometimes alienated him from officials of the Hawaiian kingdom and from his religious superiors in Europe. His mission was not only fateful, but also lonely. He drew strength from Eucharistic adoration and the celebration of the Mass, but longed for another priest to arrive so that he could receive the sacrament of confession regularly.

In December of 1884, Damien discovered that he had lost all feeling in his feet. It was an early but unmistakable sign that he had contracted leprosy. The priest knew that his time was short, so he began to finish whatever work he could on behalf of the leprosy colony before the diseased robbed him of his eyesight, speech and mobility.

Damien suffered humiliations and personal trials during his final years. An American Protestant minister accused him of scandalous behavior, based on a mistaken belief of the time that leprosy was a sexually transmitted disease.

In the end, priests of his congregation arrived to administer the last sacraments to the dying priest. In the spring of 1889, Damien told his friends that he believed it was God's will for him to spend the upcoming Easter not on Molokai, but in heaven. He died of leprosy during Holy Week, on April 15, 1889.

He was beatified in 1995 and Pope Benedict XVI canonized him in 2009.

-- Benjamin Mann, Catholic News Agency

Prayer to St. Damien

St. Damien, brother on the journey,

Happy and generous missionary,

who loved the Gospel more than your life,

who for love of Jesus left your family,

your homeland, your security, your dreams,

Teach us to give our lives

with a joy like yours,

to be in solidarity with the outcasts of the world,

to celebrate and contemplate the Eucharist

as the source of our commitment.

Help us to love to the very end

and, in the strength of the Spirit,

to persevere in compassion

for the poor and forgotten

so that we might be

good disciples of Jesus and Mary.

Amen.

— Diocese of Honolulu