BALTIMORE — The ancient Christian tradition of marking doorways with blessed chalk on the feast of the Epiphany will carry new meaning for many Catholics in 2021.

BALTIMORE — The ancient Christian tradition of marking doorways with blessed chalk on the feast of the Epiphany will carry new meaning for many Catholics in 2021.

Following a year that saw families shaken by the coronavirus pandemic, the traditional home blessing will serve as a special symbol of hope and a visible reminder of faith.

"Many have fought COVID-19 and lived to tell about it," said Michael Carnahan, a parishioner of Sacred Heart of Mary Church in Baltimore, who has practiced the chalk blessing since he was a child.

"However, many people have suffered the loss of a loved one to this virus. The chalk, along with other symbols, will be an even stronger reminder of how important God is to us and of what an important factor Jesus is in our daily lives," he said.

The blessing, popular in Poland and other Slavic countries, has spread to many parts of the world. It takes place on the liturgical feast marking the visitation of the Magi to the Christ Child and the revelation that Jesus is the son of God.

The blessing involves taking simple chalk, usually blessed by a parish priest, and scrawling doorways with symbolic numbers and letters -- this year: "20+C M B 21."

The numbers represent the current year and the letters stand for the first letters of the traditional names of the magi: Caspar (sometimes spelled "Kaspar"), Melchior and Balthazar. The letters are also an abbreviation for "Christus Mansionem Benedicat," Latin for "May Christ bless this dwelling."

Participants typically read passages from the New Testament and may sing Epiphany hymns.

Carnahan, along with his wife, Malgorzata Bondyra, and their five children, plan to take part in the tradition this Epiphany, which is observed in the United States this year from Jan. 3-8. Of Polish background, they will say the blessing in Polish and English.

"We will use this as an opportunity to remember that living a Christ-like existence on a daily basis is important to all," Carnahan said. "Just as we took for granted our health and safety as a society, we are reminded of how we might sometimes take for granted the sacrifice Jesus made for all of us."

2021 won't be the first time the blessing has taken on extra meaning. Under Soviet-dominated Poland, for example, Catholics viewed the blessing as a means of spiritual resistance.

"During communist times, Polish people would use the chalk and other symbols as a statement of their beliefs and as an indication that communism can't take away their faith," said Carnahan, a longtime member of the Polish dance ensemble, Ojczyzna, based at Holy Rosary Church in Baltimore. "It sometimes would lead to trouble for them, but ultimately it was a way to be defiant while also being true to their faith."

Will and Amy Buttarazzi, parishioners of St. Joseph Church in Cockeysville, Maryland, have also practiced the chalk blessing at their home with their eight children. As the director of family ministry at their parish, Amy Buttarazzi encourages other families to adopt the practice. She made a video about the tradition and provided written instructions.

She remembers her elementary school, the School of the Cathedral of Mary Our Queen in Baltimore, maintaining the tradition when she was growing up.

"Our principal would bless all the doors of the school building every year after we returned from Christmas break," she said. "The blessing would be written on a sentence strip and taped to the top frame of each door in the building. Now, as a mom, I wanted to continue this tradition in my own home with my children."

The Buttarazzis write their Epiphany blessing above the door of their dining room, while Carnahan and his family write it above their front door, outside.

Carnahan noted that the magi traveled far, having faith they would find the infant Jesus. They did so knowing his mission, he said.

"The chalk is a daily visual symbol for us," Carnahan said, "just like seeing the crucifix hanging on the wall, helping us to keep within us thoughts of grace, love, peace, happiness, forgiveness and more."

— George P. Matysek Jr., Catholic News Service

More online:

A guide for doing a chalk blessing at home: bitly.com/chalkblessing

Pictured: An incensing and chalking all of the doors at St. Mark Church, St. Mark School and Christ the King High School was held Jan. 4, 2020. (Photo provided by Amy Burger)

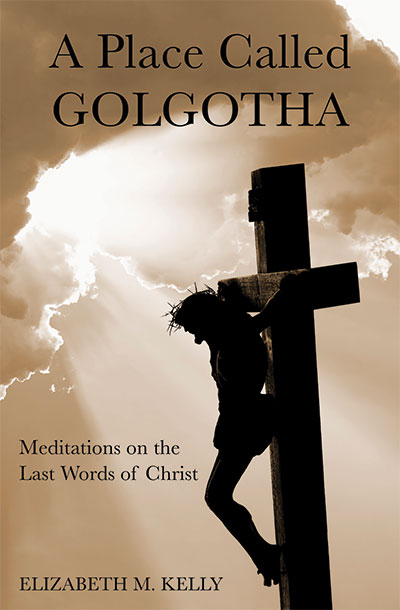

As we head into Holy Week, Christians are preparing to immerse themselves in Christ’s Passion. Meditating on the final moments of Christ’s life, and His words spoken before He surrendered His life to God the Father, can take one deeper in prayer and contemplation leading up to the joy of Easter.

As we head into Holy Week, Christians are preparing to immerse themselves in Christ’s Passion. Meditating on the final moments of Christ’s life, and His words spoken before He surrendered His life to God the Father, can take one deeper in prayer and contemplation leading up to the joy of Easter.

“A Place Called Golgotha: Meditations on the Last Words of Christ,” is the latest of 10 books by Catholic author and speaker Elizabeth M. Kelly. In this engaging and personal work, she considers all four Gospel accounts as she takes readers through Christ’s last words from the cross.

Throughout the book, Kelly weaves in stories from her own faith journey, as well as poignant and sometimes tragic moments from other people’s lives that drew them ever closer to Christ. She offers words of wisdom from the saints and creates the opportunity for self-reflection and prayer at the end of each of the seven chapters.

Kelly recently visited the Diocese of Charlotte, offering conferences during the Mary’s Women of Joy Lenten Retreat at St. Mark Parish in Huntersville, March 17-20.

Using this book on Christ’s last words as a guide, she led 150 participants on a journey of self-discovery and contemplative prayer.

“Lent is about understanding that the Father desires to change hearts,” she told the retreat participants. “It’s a turning from self and toward Him. … Part of living means carrying the cross and bringing light into the darkness.”

Kelly shared that growing up in Minnesota with farms all around, she noticed how seed planted in the dark soil would grow, breaking free of its shell, reaching toward the sun.

“It is in this manner that we approach meditating with the last words of Christ on the cross,” she said. “We enter into the darkness, trusting that there are spiritual nutrients to be extracted, nutrients that will help us grow through moments of darkness in our lives, graces and wisdom that will teach our souls to stretch upward, always in the direction of the Lord, to grow toward Him rather than away from Him to find our flourishing in His light.”

— SueAnn Howell

More online

At www.lizk.org: Order Elizabeth M. Kelly’s book, schedule her for a conference or find out more information about her blog and columns