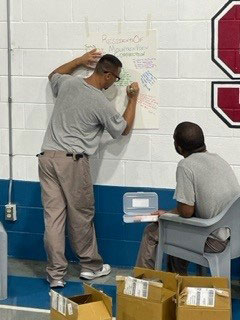

Volunteers from St. Lucien Catholic Parish in Spruce Pine display artwork created by inmates during a weekend retreat. The agenda included more than two dozen speakers, testimony from inmates, singing and musical performances, confessions, Mass, and an open house for visitors. (Photos provided)SPRUCE PINE — Inside North Carolina’s Mountain View Correctional Institution, a long gray line forms behind a microphone in the gym.

Volunteers from St. Lucien Catholic Parish in Spruce Pine display artwork created by inmates during a weekend retreat. The agenda included more than two dozen speakers, testimony from inmates, singing and musical performances, confessions, Mass, and an open house for visitors. (Photos provided)SPRUCE PINE — Inside North Carolina’s Mountain View Correctional Institution, a long gray line forms behind a microphone in the gym.

Thirty-six “offenders” – or “residents” as they are called on this special Saturday night – are clad in gray uniforms, sweating and fanning themselves as they await their turn to speak. It’s August, and the room fans are off so everyone can be heard.

Near the back of line is a young man named Joshua, aged 30, nicknamed “Monster.” He’s Native American, from the Lumbee tribe. Black tattoos cover his face and neck, among them a Carolina Panther, a Thundercat, and monster claws beneath his left eye.

As the line advances toward the microphone, Joshua listens as his fellow residents take turns describing what this three-day prison retreat with clergy and volunteers from the Diocese of Charlotte has meant to them.

“I’ve never felt like part of a family like I have the last couple of days,” a resident named Greg, tearing up, told the crowd of 75 residents, volunteers and visitors.

Another resident shared: “Just to feel like a human being again is amazing.”

Then came Joshua, who’s in prison for murder.

He was already thinking about returning to full-time prison life after the retreat, so he made a request: “Please keep us in your prayers – even when you leave.”

The next day, Joshua would make another request. This one, even more personal and enduring.

Residents Encounter Christ

The Mountain View prison retreat was part of the Catholic “Residents Encounter Christ” movement, embraced by dioceses, parishes and a variety of other religions to bring hope – and Jesus – to inmates around the world.

For residents of Mountain View, a medium-security prison for up to 884 men, the retreat was a curiosity and an opportunity. To get out of their cells. To interact with “outsiders.”

To enjoy meals from beyond the prison walls.

But what they took away from the retreat, the residents said, was so much more.

It began with this invitation: “You can spend three days in the house/cells, doing all those things you do every day, day after day. Or you can show some courage, take a risk, and see what Jesus has in store for you.”

About half of the 36 residents who signed up said they were Catholic. Others were Baptist, Lutheran, Muslim, Christian and Jehovah’s Witnesses.

“We don’t go in to proselytize or convert anyone, we just want to introduce or reintroduce the grace of Jesus,” says Rich Winslow, a devoted Catholic and retired scientist/organizational manager, who has led more than 100 prison retreats – and even initiated his own son into prison ministry: Monsignor Patrick Winslow, the diocese’s vicar general and chancellor.

“Prison ministry is a priority for Bishop (Peter) Jugis, and has always been inspiring for me since that first time my dad invited me in,” said Monsignor Winslow, who once served as chaplain in a maximum security prison in New York.

North Carolina prison leaders say they welcome programs that positively inspire inmates.

“We like to find groups that can come in and provide hope,” said Associate Warden Greg Swink. “When people come in and show they care, then there’s hope.”

The Mountain View retreat unfolded around 12 tables in the gym over the weekend of Aug. 18-20. Each table became a community of residents and volunteers, who shared stories, answered questions, and got to know one another.

An exhausting agenda included more than two dozen speakers, testimony from inmates, singing and musical performances, four meals, confessions, Mass, and the Saturday night Open House – when visitors were allowed inside the prison and residents made presentations and spoke from their hearts.

“I’m not really much into religion,” one resident said when his turn came at the microphone, “but this weekend got me thinking differently, and I just feel blessed.”

Another said: “I’ve had the devil on my shoulder for a long time. I just hope I finally got him off.”

A prison retreat, organizers say, is meant to spark a quest for Christ and Christian living among inmates and parishioners who are called to this ministry. At Mountain View, volunteers from nearby St. Lucien Parish in Spruce Pine and its mission, St. Bernadette in Linville, spent months planning and executing the retreat, under the leadership of their pastor, Father Christopher Bond.

For Joshua, the retreat was indeed a “spark,” he said.

He was 20 when he was convicted of second-degree murder in 2014. He’s not even halfway through his sentence of up to 37 years – so he needs something, he says, to help him endure.

“Being Catholic has kind of grabbed my attention because of the commitment it asks of you. You don’t just show up once a week,” Joshua said. “There is someone who can help connect you to God. I’ve learned how to pray the rosary and how to identify what I believe.”

Other inmates remained unsure about Catholicism, but said the teachings translated to their own beliefs.

A resident named Robert, serving 10 years for trafficking Fentanyl, said he came to the retreat for the food. When his turn at the microphone came, he joked about what he had received: “I got a full belly.”

Indeed, there had been pizza, barbecue, subs and fried chicken. But Robert also expressed gratitude: “I didn’t know what to expect but I’m really glad I signed up. It’s easy for me to go to the dark side...I don’t want to be there anymore.”

‘Anything can be forgiven’

Confession was among the retreat’s highlights. Prison residents and volunteers wrote down sins that weighed on them – then their papers were collected and burned. Priests placed ashes on participants’ foreheads, then after sacramental confessions in private, the priests wiped away the ashes. While only Catholics could receive the sacrament of absolution, the moment represented a cleansing for many.

Confession was among the retreat’s highlights. Prison residents and volunteers wrote down sins that weighed on them – then their papers were collected and burned. Priests placed ashes on participants’ foreheads, then after sacramental confessions in private, the priests wiped away the ashes. While only Catholics could receive the sacrament of absolution, the moment represented a cleansing for many.

Another highlight came in the tearful testimony of a seminarian: His father had died in prison, he shared, causing him great pain as a boy. It got residents thinking, they said, about the pain they’d caused their own children.

But it was the homily at Mass that was particularly piercing, said Joshua, who sat in the front row.

“I want to talk about two things,” Monsignor Winslow told the crowd. “Anger and forgiveness.”

“Anger is a human response to an injustice. (Even) the Lord got angry in the den of thieves,” he said. It’s when an angry response becomes disproportionate to the injustice, he said, “that we cross the line.”

He continued: “A disproportionate response is a lack of self-control. You can’t control your emotions.”

He then moved to forgiveness. “For every sin, we cause harm to three relationships. First, with God. Second, with the (aggrieved) person. And third, you harm the relationship with yourself.”

To be forgiven, he said, someone must absorb the sin or “pay the price to give you room to grow and change.”

“Anything can be forgiven” by God, he said, if you come to Him in a humble spirit of contrition. Aggrieved victims, Monsignor Winslow said, also pay a price for your actions. They may or may not forgive.

“Perhaps the hardest is to forgive ourselves,” he said. “We can be terribly punitive, downright punishing with ourselves…To forgive hurts, you have to feel the pain. But you must forgive yourself to grow and become different. That’s where new life begins.”

A special request

Joshua heard his own story in the homily.

Joshua heard his own story in the homily.

Reflecting after Mass, he replayed his crime.

It happened Aug. 17, 2011, when he was 18. “I shot a guy” five times in retribution, he said, because the man had beaten down a friend of Joshua’s and stolen the friend’s necklace. Looking back now, he says, “I would have never shot the guy. It was disproportionate.”

As the retreat came to a close, residents across the prison reacted.

Eighteen men signed up for classes to study the faith and follow the process for the non-baptized to enter the Catholic Church. Dozens of Hispanic Catholics who hadn’t attended but heard stories of the retreat began asking to meet with a priest, too. Father Julio Dominguez, vicar of the diocese’s Hispanic Ministry, has already answered the call, agreeing to visit the prison monthly.

Joshua made a special request, too.

“I want to be baptized,” he shared.

“I’m choosing to become Catholic with all of me, hoping I can connect with God. I’ve seen what man can do. Now I want to see what God can do.”

It’s a request Father Bond and his parish are already planning to fulfill.

Diocese and parishes ramping up prison ministry

CHARLOTTE — Across the Diocese of Charlotte, thousands of men and women are locked up in jails and prisons – and Deacon James Witulski wants to reach them all.

The pandemic hampered the diocese’s efforts to bring comfort – and Christ – to inmates within its 46 counties.

But now, Deacon Witulski and other prison ministry leaders are calling on the diocese’s 92 parishes and missions to redouble efforts to reach out to people who are incarcerated within their territories – and the diocese is there to help.

“Jesus did not forsake those who were imprisoned and of course was jailed Himself,” Deacon Witulski said. “We are called to minister to the convicted and condemned, just as we would our neighbors.”

Parishes have long formed the backbone of the diocese’s prison outreach, individually attending to nearby jails and prisons. Some priests regularly make the rounds to hear confessions, bring absolution, and say Mass for Catholic inmates. Among others, parishes and priests serving Alexander, Anson, Forsyth, Mecklenburg, Stanly, and the Triad counties have been particularly active.

The diocese launched its prison ministry with Deacon Witulski at the helm in 2019 to help coordinate, encourage and provide resources for parishes who are connecting with Catholic and non-Catholic inmates. The ministry also responds to letters from inmates, provides Bibles, and is working on plans to help inmates successfully re-enter the community.

The diocese also partners with parishes to provide weekend prison retreats, like the August visit to North Carolina’s Mountain View Correctional Institution in Spruce Pine.

“We like to meet them where they are,” said Deacon Witulski. “We talk and share and pray. We strive to talk about the mercy of God – no sin is too great for the mercy of God if one repents. It really gives them a sense of hope and dignity they may not have had for some time.”

Want to get involved?

Contact Deacon James Witulski at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. for information about participating in prison ministry within the Diocese of Charlotte.