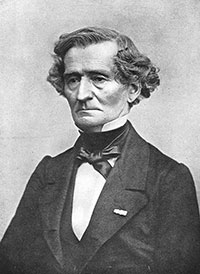

One of the most important aspects of the Christmas season is the music we hear, and over the centuries, many composers have contributed significantly to the genre. One of the more unique works is the sacred trilogy “L’enfance du Christ” (“The Childhood of Christ”) by French composer Hector Berlioz.

One of the most important aspects of the Christmas season is the music we hear, and over the centuries, many composers have contributed significantly to the genre. One of the more unique works is the sacred trilogy “L’enfance du Christ” (“The Childhood of Christ”) by French composer Hector Berlioz.

To make ends meet, Berlioz frequently resorted to writing music criticism in the typical French style: full of wit, humor and just enough sarcasm to be endearing. The same writing style is found in his memoirs. In the first chapter, in a translation by David Cairns, the composer touches upon his childhood in the faith:

“Needless to say, I was brought up in the Catholic and Apostolic Church of Rome. This charming religion (so attractive since it gave up burning people) was for seven whole years the joy of my life, and although we have long since fallen out I have always kept the most tender memories of it.”

Although lesser known among this composer’s body of work, “The Childhood of Christ” is a fine choice to commemorate the entire Christmas season. Although never referred to as an oratorio by the composer, it is considered as such by contemporary listeners. (Readers may be familiar with oratorios such as the famous “Messiah” by G.F. Handel, the first part of which is also appropriate for the Christmas season).

Berlioz started composing the work in 1850 and finished it four years later. It is scored for vocal soloists, choir and orchestra and is separated into three parts: “Herod’s Dream,” “The Flight Into Egypt” and “The Arrival at Sais.” The events in Part One do not follow Scripture chronologically. For example, Scene IV depicts Herod decreeing the deaths of the innocents prior to the scene entitled “The Manger at Bethlehem.” The latter is a duet between our Blessed Mother and St. Joseph, and since the Gospels recorded no words at the birth, a bit of creative license was used that proved remarkably effective.

Berlioz, a master orchestrator, begins “The Manger at Bethlehem” with woodwinds, including the English horn (an alto oboe) that provides an outdoor/shepherd ambience. Specific keys have long been associated with moods or emotions, and in the early 19th century, the key of A-flat major was associated with death and the grave. A composer often purposely chooses a key because of these historical associations and at first glance, one might find A-flat major to be an odd tonality for depicting the Nativity. However, as Venerable Fulton Sheen explained in his “Life of Christ,” Jesus was the only person born to die, which makes the choice of key for Christ’s birth profoundly appropriate. (A similar connection is frequently made with the Magi’s gift of myrrh.)

In the Kalmus edition of “Berlioz’s Complete Works,” the translation of Mary’s lullaby reads: “Sweet, holy babe, these sweet herbs so tender give the sheep thou lovest … see they come to Thee bleating! They are so meek. Let them graze on the meadow, lest they shall suffer hunger.”

One can clearly see the powerful references to Christ’s future role as the Good Shepherd in the choice of text here. She is subsequently joined by St. Joseph before the scene ends with an unassuming, instrumental conclusion.

Berlioz is frequently heralded for his great dramatic prowess, but this section of the “L’enfance du Christ” demonstrates his sensitivity and is a perfect representation of the peaceful Nativity of Our Lord.

— Christina L. Reitz

Listen online

Listen to a rendition of Hector Berlioz’s “L’enfance du Christ”