Choosing the ‘Beautiful Way’

GREENSBORO — It was a storybook scene. Amid the stately residences, peaceful park and majestic trees of her Sunset Hills neighborhood, Mary Van der Linden, one of seven children, walked to and from her elementary school each day. Perhaps the only feature to rival the beauty of her daily journey, whether on foot or wheels (after her family moved), was the destination – the striking Gothic architecture of the neighborhood’s Catholic church, where her family worshiped and the children attended school.

GREENSBORO — It was a storybook scene. Amid the stately residences, peaceful park and majestic trees of her Sunset Hills neighborhood, Mary Van der Linden, one of seven children, walked to and from her elementary school each day. Perhaps the only feature to rival the beauty of her daily journey, whether on foot or wheels (after her family moved), was the destination – the striking Gothic architecture of the neighborhood’s Catholic church, where her family worshiped and the children attended school.

It was Our Lady of Grace, an ideal setting for Van der Linden as she unknowingly began her quest to reveal another kind of beauty – one that would culminate in the publishing of her first book, “Beautiful Way,” in 2022. At the school, the students did a lot of writing. Van der Linden was encouraged by her teachers and won an essay contest in eighth grade about the school’s uniform policy.

“Writing a book has been a dream of mine since I was young,” said Van der Linden. “Our Lady of Grace School influenced me a lot as a writer. Multiple times I can think of in fourth, seventh and eighth grade I had teachers tell me that I have a flair for writing, and that did so much for my confidence. I’ve had that in the back of my mind – that I’m a decent writer – and all these years later my Catholic education is still having an impact.”

“Beautiful Way” is a coming-of-age story that follows two teenage girls as they learn to navigate other cultures and religions, bullying, newfound interests, and seeing others for who they are rather than what is on the surface. The story began forming when Van der Linden’s daughter Claire was dealing with typical social and best friend issues in the third grade.

Van der Linden began telling Claire a bedtime story to help her learn to develop new friendships. The story grew in detail and popularity over time, and Claire even asked her mother to share it during one of her sleepovers. The result, some 20 years later, is “Beautiful Way,” which follows eighth-grader Natalie as she welcomes her new neighbor Patrizia Bellavia (“beautiful way” in Italian) to their Greensboro school.

Patrizia is from an Italian Catholic family. The inspiration for the Bellavia family is a collection of many experiences and people Van der Linden has known through the years, along with the author’s rich imagination. Van der Linden’s parents always welcomed exchange students, and Van der Linden herself spent time as an international student living with her good friend Tita and her family after they moved to Caracas, Venezuela. Tita and Van der Linden met at Our Lady of Grace and are still close friends today.

In the book, Natalie and Patrizia become fast friends, despite their differences, and they even carve out a path in the woods between their homes. The two learn and grow together as they face bullying, unfamiliar customs and religious practices in the Catholic and Jewish faiths, and the brokenness that is universal to the human condition as they come to a deeper understanding of a difficult loss suffered by a classmate and his family.

“If we are truly worshipping God and practicing our faith, we are being inclusive to others, we are being kind, and we are being loving toward our brothers and sisters in humanity. It was really important for me to have that be a theme in the story,” Van der Linden said.

In the book, Van der Linden adeptly covers difficult territory as Patrizia introduces the rosary to Natalie, whose family is Methodist.

“In my adult life as a Catholic, I came to understand and love the rosary, and I really wanted to explain why Catholics pray the rosary to the best of my ability to somebody who thinks it’s weird,” she said.

Mary Van der LindenNatalie and Patrizia also gain an appreciation for Jewish customs when the two visit their friend Josh’s house for Chanukah and discover the richness of the faith and its connections to their own, something Van der Linden has come to understand well through her interfaith marriage. The differences have enriched her life, she said, while she continues to grow in her Catholic faith.

Mary Van der LindenNatalie and Patrizia also gain an appreciation for Jewish customs when the two visit their friend Josh’s house for Chanukah and discover the richness of the faith and its connections to their own, something Van der Linden has come to understand well through her interfaith marriage. The differences have enriched her life, she said, while she continues to grow in her Catholic faith.

“The Sacred Heart of Jesus is what defines Catholicism for me, and that is the core of our faith – that is the Communion, the heart of Jesus,” Van der Linden said.

“Everything was made through Him, so every person of a different faith, different color, different status was made through Him, and I really wanted to make sure that whatever I put out there had that reflection of how Jesus sees us, not so much how we divide ourselves.”

— Annie Ferguson

Get a copy

To order a copy of “Beautiful Way,” go to www.barnesandnoble.com or www.amazon.com or email Mary Van der Linden at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Although the feast of St. Francis on Oct. 4 is not often associated with music, there is a connection.

Although the feast of St. Francis on Oct. 4 is not often associated with music, there is a connection.

In the 19th century, a major shift occurred in music. As composers craved to express their art on a different level from that of the traditional “absolute music,” many began writing “program music” – that is, instrumental music that tells a story.

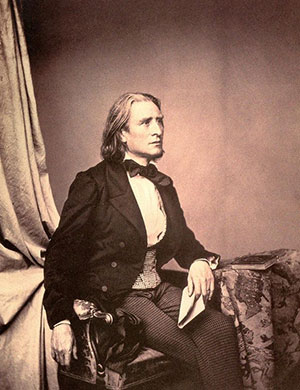

One of the masters of this genre was Franz Liszt (1811-’86), a Hungarian pianist who took Europe by storm with his unmatched technique. Although he is well-known for his significant contributions to music history, many are surprised to learn that he was a devout Catholic. While the feast of St. Francis (Oct. 4) is rarely associated with music, the first of Liszt’s “Deux Légendes” is based on this beloved saint.

Liszt was raised in the Catholic faith. His father wanted to be a Franciscan and named his son after the order. After an incredibly successful career, Franz moved to

Rome in 1861 to marry Princess Carolyne Sayn-Wittgenstein, but the annulment for her first marriage fell through, and the idea was abandoned. He stayed in the

Eternal City and pursued the minor clerical orders, subsequently being referred to as Abbé Liszt.

While in Rome, he composed “Deux Légendes” (“Two Legends”), the first entitled “St. Francois d’Assise-La prédication aux oiseaux” (“St. Francis of Assisi – the Sermon to the Birds”), inspired by Chapter 16 of “The Little Flowers of St. Francis of Assisi.” The Dover edition, translated by Thomas Okey, states: “My little sister the birds, much are ye beholden to God your Creator, and always and in every place ye ought to praise Him (…) God feedeth you and giveth you the rivers and the fountains for your drink; He giveth you the mountains and the valleys for your refuge, and the tall trees wherein to build your nests (…) wherefore your Creator loveth you much, (…) and therefore beware, little sisters of mine, of the sin of ingratitude, but ever strive to praise God.”

The 1966 Breitkopf & Härtel edition of the score includes Liszt’s own humility-filled preface: “My want of facility, and perhaps also the narrow limits of musical expression possible in a little work of small dimensions (...) have obliged me to restrain myself, and to greatly diminish the wonderful profusion of the text of the ‘Sermon to the little birds.’ I implore the ‘glorious poor servant of Christ’ to pardon me for having thus impoverished Him.”

By basing the work on this account, Liszt combined literature, nature and religion – all aspects that fascinated Romantic composers. The composition is for solo piano beginning with high notes to represent birds singing. They call back and forth before breaking into song, but when St. Francis begins to preach, a lower register of the piano is used to depict a man’s voice. A dialogue ensues between the saint and the birds, presented by low and high registers, respectively. Soon, the birds become so impressed with St. Francis’s preaching that they cease singing entirely to listen.

St. Francis is always associated with animals and nature, making him one of the most beloved saints in our history. (Our own family dog, Charlie Chuckles, wears a blessed St. Francis medal.) A popular quote erroneously attributed to St. Francis is “Preach the Gospel at all times. When necessary, use words.” Although there is no evidence he actually said those words, it is certainly applicable to the first of Liszt’s “Deux Légendes.”

— Christina L. Reitz

More online

Listen to Liszt’s “Légendes” and read further details on the composition: