Original writing from America’s first saint inspires courage, faith

CHARLOTTE — The critically acclaimed “Cabrini” movie left many wanting to learn more about the Italian nun and future saint who crossed the Atlantic to battle deeply rooted prejudice, dire poverty and her own illness to give Italian immigrants a better life in New York City at the turn of the century.

CHARLOTTE — The critically acclaimed “Cabrini” movie left many wanting to learn more about the Italian nun and future saint who crossed the Atlantic to battle deeply rooted prejudice, dire poverty and her own illness to give Italian immigrants a better life in New York City at the turn of the century.

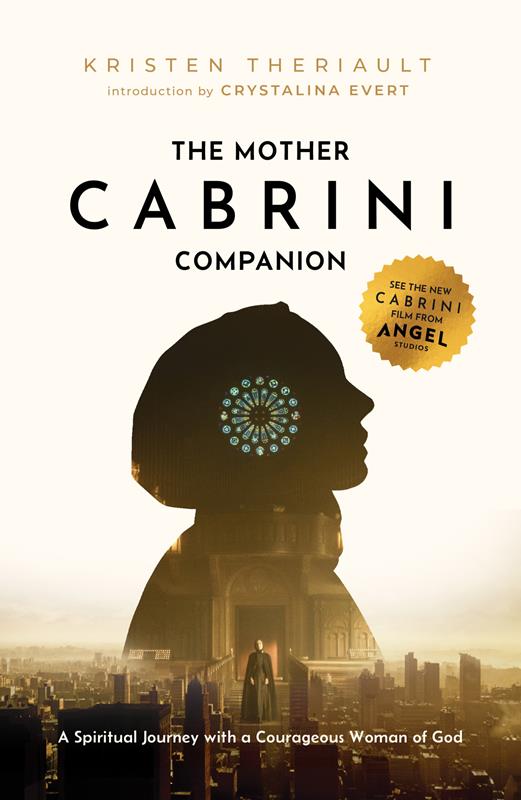

Now viewers can hear from St. Frances Xavier Cabrini herself in “The Mother Cabrini Companion: A Spiritual Journey with a Courageous Woman of God” by Kristen Theriault of Sophia Institute Press. The April 9 release was created in collaboration with Angel Studios, which brought Mother Cabrini’s story to the big screen, illustrating her boldness in building an orphanage and hospital in New York City and eventually others around the world.

However, like many Catholics, Theriault, who is editor of Catholic Exchange and author and media spokesperson at Sophia Institute Press, wasn’t fully aware of the story of the first canonized American saint until viewing the film. She soon became an expert after delving into Mother Cabrini’s own words for the companion, an important complement to the movie.

“Mother Cabrini was someone who existed at the periphery of my consciousness, and I knew she was the first American citizen to be canonized, and I knew vaguely about her work in New York but never with such immediacy until I took on this project,” she says.

“I’m very grateful for that because her life is so inspiring, and it sheds light not only on the spiritual aspect of her life but also her humanitarian work. It gives a very interesting snapshot of the turn of the century in New York City and really in all American cities.”

By compiling letters from Mother Cabrini’s international travels and her spiritual retreat notes, Theriault opens a window into Mother Cabrini’s spirituality. Poetic descriptions of creation, the sacraments, the virtues, and the joys of heaven console, encourage and edify those who desire to take this spiritual journey.

Theriault recently spoke with the Catholic News Herald about what to expect from the book and the wisdom she gained in the process of writing it:

CNH: How did the idea for this book originate?

Theriault: Sophia Institute was approached by Angel Studios a few months ago, and we compiled this in less than a month. We wanted to do some companion books to the film, so I was tasked with writing a devotional for Mother Cabrini, and to do this I looked at the primary sources.

CNH: What kind of primary sources did you find?

Theriault: There are quite a few letters she wrote. Many of them are to her sisters from her travels abroad, so after she founded this orphanage and hospital in New York City, she of course went on to found dozens of others throughout the entire globe. I was able to read letters that she wrote home to her sisters while she was traveling, and they’re very inspirational because they are quite full of encouragement and lots of meditations on her missionary vocation. At this time, she was still serving as their spiritual mother while she was physically away from them, so they have a lot of spiritual guidance and direction in them.

Her writings lend themselves well to a devotional of this kind because it touches on many universal themes of the faith. I also used her retreat notes, which is called ‘Journal of a Trusting Heart.’ These are more introspective because she’s writing to herself. One common theme that emerged from both of these is her idea of conversion as something that is an ongoing process.

She believed in conversion as something that was first and foremost within the heart, so even someone with her degree of holiness, she considered herself to not be fully converted. She was always seeking to grow deeper spiritually, to a deeper relationship with God.

CNH: How was Mother Cabrini’s faith intertwined with her humanitarian work?

Theriault: She really embodied both the corporal and spiritual works of mercy, and ultimately this is what we see with saints. They are focused on eternal life first and foremost, and they take very seriously the call to love God and to love their neighbor as themselves. They don’t really favor one over the other – humanitarian work versus conversion. They view it as all one and the same, all working toward the same goal. If you’re not familiar with her more spiritual writings, it might not come through as much in the film, so that’s why I think this book is such an important supplement. It fills in those gaps.

TheriaultCNH: How do you think Mother Cabrini’s writings can reach people of other denominations or of no particular faith?

TheriaultCNH: How do you think Mother Cabrini’s writings can reach people of other denominations or of no particular faith?

Theriault: When she was traveling on ocean liners at that time, passengers took quite a deferential attitude to her, whether they were Catholic or not. Protestants who were prominent in their communities, especially Anglicans, would be so respectful of Mother Cabrini and of her sisters. The captain would often invite them to dine privately with him on board, which is pretty much the highest honor you can get on an ocean liner.

Whether that is through her personal presence or this beatific peaceful calm that she had within her, or from her reputation that she had garnered as someone who gets things done in the in the realm of her charity, Mother Cabrini was able to connect during her lifetime with people who were not Catholic and to plant those seeds with them, or at least mirror charity toward them.

CNH: How would you describe Mother Cabrini’s writing?

Theriault: The letters in the beginning of the book are her meditations on the beauty of creation and nature. She had a knack for making spiritual allusions to the natural world, using romanticism of nature and how it reflects the soul and vice versa. For example, if the steamship she was on had just gone through a storm, she likened the state of the sea in turmoil to that of the soul in the state of sin, and then if the ship passed through the storm into sunshine, she likened that to a soul in the state of grace and the tranquility that comes with a clear conscience. She had this very poetic imagery that she always tied back to the spiritual life.

CNH: Do you think Mother Cabrini’s story can help mend some of the divisions of our day?

Theriault: It will take a lot of examination of heart and really an internalization of her words. Then, yes, they can have that effect. The Church is highly involved in advocating for immigration, marginalized groups such as the unborn, and others. If Mother Cabrini were alive today, I think she would certainly not be silent on these issues, emboldening people to seek the truth and not to be content with the status quo.

Mother Cabrini quoted one of her favorite saints, St. Francis Xavier, from whom she took her middle name. He was a missionary, too. I’ll paraphrase his quote, but he said something about missionary zeal needing to be tempered with love, charity and kindness. Zeal without charity is somewhat empty and can come off as patronizing, yet zeal with charity is perfect because it shows that it’s motivated from a love of the other. If we can adopt Mother Cabrini's ability to see human beings as individuals instead of statistics or groups (the way the bureaucracy of her time viewed human beings), if we can instead restore that dignity, I think that will go a long way to solving a lot of these current issues.

CNH: What do you think fueled Mother Cabrini’s courage and perseverance?

Theriault: She had an attitude of joy and acceptance. In addition to the persecution she endured, there was also her own health – something she struggled with her whole life. She had tuberculosis as a child, and that blocked her entry into several convents before she eventually founded her own order. Her health condition was just an accident of nature but something that would have held her back if she hadn’t been so tenacious. She carried that determination forward whenever there was a man-made roadblock in her way, too. She trusted God and never gave up.

Sophia Institute Press and Angel Studios have also published a special edition of “The World is Too Small: The Life and Times of Mother Cabrini” and a children’s book titled “Mother Cabrini: A Heart for the World.” For more information and to order these and the devotional companion, visit www.sophiainstitute.com.

— Annie Ferguson

The sweet side of suffering

Patrick O'HearnLINCOLNTON — Pain and sorrow are top of mind during Lent as Jesus’s Passion draws near. They are difficult topics, but like a true mother, Our Lady of Sorrows soothes the sting of her children’s suffering in whatever form it may take through her own “dolors” or sorrows.

Patrick O'HearnLINCOLNTON — Pain and sorrow are top of mind during Lent as Jesus’s Passion draws near. They are difficult topics, but like a true mother, Our Lady of Sorrows soothes the sting of her children’s suffering in whatever form it may take through her own “dolors” or sorrows.

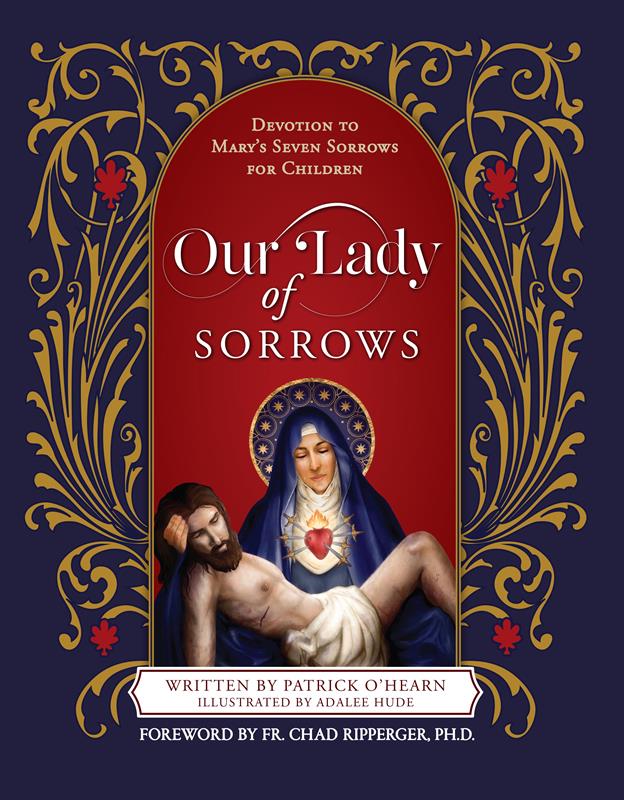

Perhaps no one understands this better than Patrick O’Hearn, a Catholic husband, father and parishioner of St. Dorothy Church in Lincolnton. He has been devoted to the Blessed Virgin Mary under her sorrowful title since childhood and is the author of seven books, including his most recent project, “Our Lady of Sorrows: Devotion to Mary’s Seven Sorrows for Children,” a new release from Sophia Institute Press.

“Mary is the secret to the best Lent ever because she understood Jesus’s pain more than anyone, so I believe she takes us by the hand and walks with us through these sorrows, but then at the end we’re consoling Jesus,” O’Hearn says. “It is the perfect book during Lent because it really helps us enter into the mystery of suffering in a beautiful way.”

Because the devotion waned in popularity since its inception during the Middle Ages, O’Hearn says he felt called by Our Lady to introduce her seven sorrows to new generations to help them navigate the inevitable sufferings of life, grow in virtue and strengthen in faith.

The Church observes two feasts in honor of the Seven Dolors of Mary – one on the Friday before Good Friday and the other on Sept. 15. The devotion itself includes a short introductory prayer, then a prayer for each of the sorrows, followed by a request for the given virtue and gift of the Holy Spirit, ending with a Hail Mary each time and brief concluding prayers after the seventh sorrow.

The sorrows include the Prophecy of Simeon, the Flight Into Egypt, the Loss of the Child Jesus in the Temple, Mary Meets Jesus on the Way to Calvary, Jesus Dies on the Cross, Mary Receives the Dead Body of Jesus in Her Arms, and Jesus is Placed in the Tomb. Great graces and heavenly favors are promised to those who pray the devotion.

“I’ve felt Mary’s presence throughout my whole life, protecting me from a lot of evils, so I think that writing this book was a way for me to say thank you to her for all she’s done for me,” O’Hearn says.

In the book, young readers will find Scripture, meditations and prayers for each mystery, aimed at helping children overcome fear, worry and doubt, develop virtues such as faith, courage and perseverance, and reflect on the life of Jesus.

In the book, young readers will find Scripture, meditations and prayers for each mystery, aimed at helping children overcome fear, worry and doubt, develop virtues such as faith, courage and perseverance, and reflect on the life of Jesus.

Included in each sorrow is a reflection in which Mary speaks to the child, and then there’s a prayer to ask Mary for the virtue associated with the sorrow. O’Hearn says the work can be considered a devotional or mediational book. It also contains a collection of traditional prayers in English and Latin as well as four original prayers by Father Chad Ripperger that children can pray daily to grow closer to Our Lady and for their vocation and protection.

“I’ve always been drawn to the image of the seven sorrows,” O’Hearn says. “It took on greater depth throughout the course of my life, but I’ve always been drawn to her image of the swords in her heart. As a boy, I thought that was cool.”

As he grew, O’Hearn relied on Our Lady of Sorrows while he spent nearly three years in a Benedictine monastery and ultimately discerned out of religious life and into married life. When he and his wife Amanda lost two of their children to miscarriage, it was his devotion to the Seven Sorrows of the Blessed Virgin Mary that helped ease the pain.

“I think any woman – or man – can identify with Our Lady of Sorrows more than I think any other title because she’s suffering and she’s standing by her Son, and as parents we don’t want to see our children suffer. It’s that element that makes her so relatable to us.”

Order and learn more

At www.sophiainstitute.com: Buy a copy of “Our Lady of Sorrows: Devotion to Mary’s Seven Sorrows for Children.”

At www.patrickrohearn.com: Get to know the author and St. Dorothy parishioner

— Annie Ferguson